Fantasia‘s a masterpiece but it’s also a movie that I can’t imagine ever watching from beginning to end without falling asleep. It’s too relaxing. It’s the first movie on the List that blends live action with animation — and the seamlessness with which the two forms fit together — which you have to imagine sounded like a batshit creative idea in the early 1940s — bears testament to the devotion of Walt Disney and his partner on the film, composer Leopold Stokowski (Disney did produce a series of animated shorts in the late ’20s and early ’30s that featured a little girl named Alice interacting with animated figures, but it was way more low-tech, silent, silly).

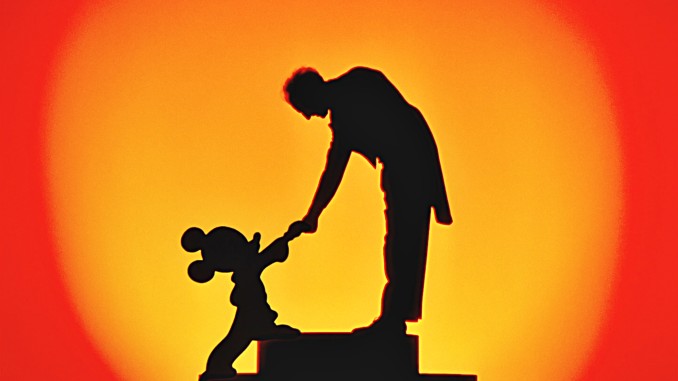

Fantasia, though very much its own unified experience, is a compilation of Disney shorts (the first and most famous, “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice,” featuring a magical Mickey Mouse at the mercy of a sentient, mischievous mop — it was also the shoehorn segment that got Walt so immersed in making the movie) strung together with live classical performances. The musicians, dapper and silhouetted against gorgeously ambient technicolor backgrounds, sit by while conductor Deems Taylor interacts with Mickey and addresses the audience personally.

Fantasia is tough to write about for a couple reasons. First of all, there isn’t much of a story. It’s built on the ecstasy of the music and the visuals — the visuals are complex and I’m still the sort of amateur writer who’d take (who’d need?) pages and pages to describe them. Even more intimidating is teh prospect of writing constructively about music, of which I know nothing and on which I’ve only ever read or written stuff as it pertained to Leonard Cohen.

But I can gab about its reception!

There are two interesting camps in the film’s negative reception: the first is comprised of critics and audiences who were turned off by the inclusion (the celebration) of classical music. They felt it was pretentious. After that there’s the camp of critics (“music men,” in the derisive words of writer Pare Lorenz) who knew a thing or two about classical music, didn’t like what they were seeing in the film, and wanted Mr. Disney to get back in his box, stop trying his hand at high-culture stuff, get back to scribbling mice. Some of those music-inclined critics felt that the music in Fantasia was just bad while others thought that the eminence and genius of those works were being demeaned by having to share the stage with dancing cartoon hippos.

Not knowing a thing about classical music myself, the only verdict I can give is that the movie looks really beautifully. I found myself smiling at it in a way I hadn’t been smiling with Snow White. And I think that the music is a beautiful complement to those very beautiful images — and not just the images of the classical, plump, cherubic-looking Disney characters but also the abstract passages: the pulses and plumes and spirals of color that stream along with the rhythm. It looks like it would be the most wonderful thing to project on your bedroom ceiling late at night (TCM’s notes on Fantasia mark its resurgent popularity in the late 1960s, with the rise of psychedelic drugs).

I’ve mentioned in a few essays already that I have a tough time getting excited about harmless movies like t his, where the narrative feels sanitized and like there’s nothing at stake, and so I came into Fantasia feeling skeptical, like I was having to steel myself for something tedious. But I actually found it really lovely and warm and fun. Granted, I think that the last segment, featuring centaurs and cherubs in a mystical forest, runs a bit long and lavishes too much aint-they-cute attention on these babies and their dramatic blinking. Their long lashes. But otherwise it’s great! Researching the innovations of Disney’s sound engineers for this film (the use of “Fantasound,” a 7,000-pound setup of special speakers in different parts of the theater) is as mystifying as it is awe-inspiring — and reminiscent of the warm vibe I got, not that long ago, while reading of the heartfelt creative labor that went into the production of Snow White, which by the end of production had logged over 200 years of man hours from the crew.

I’m looking at Fantasia now in almost the same way I looked at Leni Riefenstahl’s Olympia. Not that it stands beyond criticism, but just that its strengths and value go way beyond what I can perceive as a casual viewer. I don’t mean to say that it’s flawless or that i don’t have a right to dislike it — just that, going into it with an understanding of its innovation and the labor behind it, I feel like I owe it a little more consideration than I usually might. To give it a second chance if at first it proves a bit tedious.

3 comments